by Finlay MacDonald

from Sunday Star Times

14 February 2010

One should always be wary of seemingly simple solutions to seemingly intractable problems – especially solutions endorsed by Bono. Yet the idea of a "Robin Hood tax" on global financial transactions, despite appearing almost too good to be true and, yes, backed by U2's blathering messiah of world peace himself, really is hard to fault.

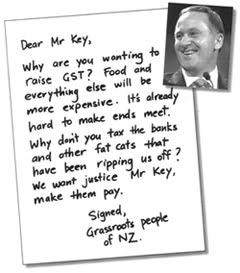

From a New Zealand perspective the launch of a fresh campaign for such a tax was beautifully timed, coinciding as it did with the timid revenue tinkering proposed by the prime minister. If you'd found yourself drifting off listening to John Key's uninspiring prescriptions, you could have hopped on YouTube and watched the snakily funny Bill Nighy video in which he plays a smarmy banker failing to justify his opposition to a Robin Hood tax.

Like most bankers and tax experts who thrive on the perceived complexity of their fields, simplicity and common sense is his enemy. The central genius of the Robin Hood idea is that it treats the global financial system for what it really is – an economic activity that can be taxed like anything else. Indeed, since so much of the world's total corporate profits now derive from unproductive speculative trades and other money-go-rounds – a phenomenon sometimes described as the "financialisation" of the economy – it's long overdue for scrutiny.

The idea is not particularly new, but it gained new impetus with the global financial crisis and the debate about longer-term remedies for reckless investment banking and foreign exchange dealing. The primary purpose of such a tax, in fact, would be to take some of the heat out of money markets and reduce exchange rate volatility. As its original proponent James Tobin put it, it would "put sand in the wheels of international finance" by creating a major disincentive to short-term speculative transactions.

One benefit of this – aside from curbing the sort of market panics that trigger major crises and ruin ordinary people's lives – would be the diversion of investment back towards the productive sectors. Also, and not least, it would raise the kind of money that makes a difference to the worthy goals humanity (and Bono) aspires to, like fighting poverty and climate change.

Of course, if successful, such a tax would reduce its own potential revenue base, which is why estimates of what it might generate are problematic. However, given that roughly $1.5 trillion is traded in world currency markets each day, even a significantly reduced amount would yield a hefty annual tax take. And it's not as if anyone is arguing for a regime so punitive it would put forex dealers out of work and shut Lamborghini showrooms. Suggestions of between 0.05 and 0.25 percent could raise between $90 and $300 billion a year, depending on the forecast. According to a report by liberal think tank The New Economics Foundation, quoting previous expert analysis including research by the IMF, a currency transactions tax is administratively and logistically feasible – albeit dependent on international political co-operation.

Well, there had to be a catch. Getting governments to agree on such a policy when they are so much in thrall to their domestic financial lobbies would be about as easy as achieving that other noble goal, world peace. British Prime Minister Gordon Brown advocated such a tax at the G20 meeting late last year and continues to promote the idea. Yet only last month the governor of the Bank of England humiliated him by dismissing the proposal as "bottom of the list" of reform options.

In the US, source of the present crisis (which is far from over), Wall Street has very effectively blocked all attempts at reform, historically and now. It's brazen and shameless – how else to explain a banking sector that could revive its morally obscene bonus culture within months of being bailed out with billions upon billions of public dollars? Expecting such creatures to act other than purely self-interestedly is futile.

Outside the banker bubble, though, there is plenty of support for a Robin Hood tax, including from industry leaders, who actually make and sell stuff.

As the boss of New Zealand fishing giant Sanford said to shareholders just the other day, "A tax on non-trade-related currency transactions could not only earn significant income for the government, it could also result in our exchange rate moving closer to its realistic value and thereby add significant value to the wealth of New Zealanders." Now there's a tax reform plan with genuine vision – precisely why this government and its former merchant banker boss could never come up with it.

finlay.macdonald@star-times.co.nz

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment